Sept 22, 2010

OP-ED CONTRIBUTOR

Ominous clouds are gathering over Ban Ki-moon, the beleaguered Secretary General of United Nations, at a time when he must soon announce whether he intends to seek a second, five-year term of office. And Ban’s problems are the U.N.’s problems. The Copenhagen climate change debacle, the devastating recent report of his departing audit watchdog, Inga Britt-Ahlenius, who likened the UN under Ban Ki-moon’s leadership to a ship left rudderless in the wind, and the growth of new organizations, such as the G-20, to manage global economic problems, indicate that the organization is destined for irrelevancy in the emerging global geopolitical order unless strong leadership makes it relevant again.

Within the corridors of the UN, it is well known that Ban Ki Moon works from dawn to dusk and expects the same from his closest associates. However, all this hard work has not silence the growing number of skeptics, who feel that the global influence of the organization under his leadership is eroding day-by-day.

The U.N. Secretary General’s job has one of the most impossible on the planet. It requires intellectual, managerial and spiritual depth, qualities seldom found in one person. Dag Hammarkskjold, the second Secretary General, is generally seen as someone who possessed those attributes, a man of high intelligence and managerial competence but also willing to stand up unflinchingly for his principles. This earned him and the organization much respect. Hammerskjold is also widely seen as a miraculous exception in the history of his post.

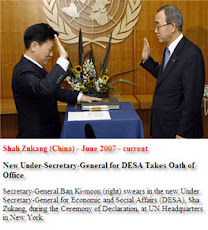

Unlike Hammarskjold or even his own immediate predecessor, Kofi Annan, Ban Ki-moon has not been able to forge such a reputation, but is instead generally seen as a follower. This reputation has become Ban Ki-moon’s Achilles heel. He needs to challenge the perception that he is a faceless bureaucrat with no ideas of his own and demonstrate a capacity to stamp his authority in a positive fashion on the world body, if he is to deserve a second term. Ban Ki-moon is in urgent need of reinventing himself through a series of decisive moves.

Firstly, he should undertake across-the-board overhaul of his senior management team. There is a strong sense that the team assembled by Kofi Annan was vastly superior to the one serving Ban Ki-moon. As Inga-Britt Ahlenius pointed out last month in her unprecedented and devastating “end of mission” letter, many members of Ban’s team have little expertise in their respective areas, and with a few exceptions, are widely seen as under-performing.

Ban desperately needs to reverse this impression. This would send a clear message to Member States and staff alike that merit and competence is central to the realization of the organization’s mission.

Secondly, Ban Ki-moon should undertake a rapid capacity assessment of every department in his Secretariat. The inefficiency and underperformance of the U.N. is legendary, as is its resistance to change. It is essential for Ban Ki-moon to strengthen his leadership of the Secretariat by doing an inventory of its weaknesses and fostering greater unity of purpose among the highly decentralized departments.

Thirdly, Ban Ki-moon should establish a high-level panel of eminent person to provide real, concrete recommendations on how to make the organization truly transparent. This is probably the single most important issue affecting the effectiveness of the world body. All such attempts have so far failed. But the desire to finally achieve those goals, especially among the relative handful of states which provide most of the U.N.’s operating funds, is stronger than ever. Ban needs to get in front of this movement in ways that he has so far failed to do.

If not, the U.N. will be made more irrelevant than it already is now. Models of international cooperation at the global and regional level have rapidly changed in the past decade as the pace of economic globalization has accelerated. These processes have not only led to the creation of the G-20, but also significant strengthening of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the emergence of such increasingly effective regional policy forums as Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, ASEAN, and the African Union.

The rising powers of the developing world are gaining increasing stature in those institutions. China, for example, has become a major force in ASEAN, even as it has become the second largest donor to the World Bank.

What this threatens to do, unless Ban takes a stronger hand, is give more radical but less powerful nations, such as Libya, Iran and Venezuela, greater leverage in the ageing and inefficient structures of the U.N., and even newer innovations such are the Human Rights Council or UN Women Organization. This has introduced a new threat to the organization’s existence: most other member states are growing increasingly tired of being held hostage to the extreme views advocated by such outlying countries, and the high cost of coordination associated with maintaining internal dialogues with them.

A strongly led, open and efficient U.N. administration would go a considerable distance toward redressing this balance.

Finally, Ban Ki-moon should drastically reorganize and revitalize his expensive and inefficient communications machinery. At present, most of it is organized around the idea of defending the U.N. from the world’s press, rather than engaging with it to promote the organization’s goals. Ban is notoriously an uninspiring public speaker and all attempts to make his image sexier, in the model of Kofi Annan, have been failures. What he needs instead are talented, widely respected communicators who can speak freely on his behalf, with the knowledge that the Secretary General has their back.

To lay out these sweeping changes is to acknowledge how difficult they are. But difficult is not the same as impossible. A Secretary General who dared to try them would be a Secretary General the world would like to see continue in office.

No comments:

Post a Comment