CLICK HERE TO VIEW THIS STORY ON POLITICO

By: Darren Samuelsohn

July 5, 2011 10:35 PM EDT

President Barack Obama faces several big green tests over the next year on the international stage.

Environmentalists and foreign allies are clamoring for U.S. leadership from the Nobel Prize winner on a pair of upcoming summits focused on global warming, sustainable development and biodiversity.

But the White House will need to temper expectations on its foreign policy as it fends off Republicans eager to keep Obama from winning a second term.

U.S. officials say a presidential trip to Rio de Janeiro for the 20th anniversary of the Earth Summit in June 2012 isn’t on his schedule right now, although they can expect the drumbeat to grow for Obama to change those plans as the U.N.-sponsored conference gets closer.

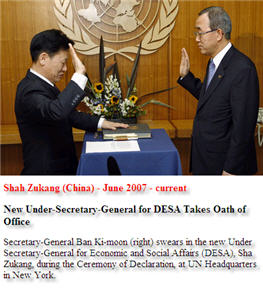

“The United States of America is a country that people around the world admire for its can-do attitude,” Sha Zukang, a Chinese diplomat and the top U.N. official connected with the Rio summit, said last week during a visit to the National Press Club in Washington. “Here, people believe that no problem is too big for human ingenuity to solve. The world has never needed that ingenuity more than it does today. The world needs your leadership.”

On the other hand, conservatives are giddy at the idea of Obama jetting to a South American seaside capital in the middle of his reelection campaign.

Earlier this year, they mocked the president after he praised Brazilian oil drilling efforts while on a visit to Rio, using his remarks in online ads that questioned his commitment to domestic energy exploration.

Republicans also carry big doubts about the climate science at the center of the international talks and question why a debt-strapped United States should spend any money abroad on environmental issues.

“Having some foreign gala with a bunch of rich people flying in private jets and demanding the United States have a lower standard of living is probably not the way, getting into a presidential election, to speak to a country with 9 percent unemployment,” said Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform.

Obama won’t be the first president to deal with such an international environmental dilemma.

In 1992, amid his own reelection campaign, President George H.W. Bush agreed to make a last-minute trip to Rio’s first Earth Summit as diplomats neared a major agreement that set up the underlying structure for all future global warming negotiations.

Greens cheered Bush for the move, but there was still criticism that he insisted on inserting language to make the pact voluntary and also didn’t sign a separate treaty on biodiversity. That fall, environmentalists went in large numbers for Bill Clinton.

Ten years later, President George W. Bush skipped the next major global sustainable development summit in Johannesburg, South Africa. A local newspaper there published a cartoon of the U.S. leader mooning the world. Secretary of State Colin Powell attended and was heckled.

Environmentalists cheered Obama’s 2009 decision to attend climate change negotiations in frosty Copenhagen, Denmark, which drew a record number of presidents and prime ministers. They hope the Democrat doesn’t cave to conservative pressure now.

“[Republicans are] a powerful political force in the United States, but the world isn’t going to sit still for the United States to go through another election cycle,” said Jacob Scherr, director of global strategy and advocacy at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Even if Obama doesn’t go to Rio, the United States will have considerable presence at the conference and in the preliminary legwork leading up to it.

The White House and State Department are already leading an internal working group on the Rio conference with about 15 agencies, including the EPA, the Energy and Commerce departments, the U.S. Trade Representative and the U.S. Agency for International Development.

“We look at Rio as an excellent opportunity to bring the world community together, to give a lot of energy and activity toward promoting sustainable development into the future,” a senior U.S. official said.

Unlike Rio’s 1992 Earth Summit, there will be no treaties or other binding agreements on the docket. Instead, the plan is to produce about three pages of consensus text among the more than 190 countries in attendance.

Roundtable talks will focus on getting individual countries to merge green issues with their economic development. There are also sure to be discussions about ocean acidification, protecting dwindling fisheries and cleaning up manufacturing supply chains.

Private companies, state and local officials, and a large contingent of environmental and nongovernmental organizations are expected at the three-day conference, which U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon has said “will be one of the most important meetings in the history of the United Nations.”

The Rio summit comes as the world population nears 7 billion and global food and water shortages cause repeated bouts of political turmoil. Demand for energy keeps growing, with a billion cars on the road and about 1.4 billion people who still lack access to electricity.

Mounting scientific evidence that fossil-fuel emissions are changing the planet’s climate in irreversible ways also poses a big test for world leaders who must deal with immediate demands to restore fiscal order.

“Our test is to green our economies, … to reduce emissions and seek clean-energy growth,” Ban said in May. “How? By connecting the dots among climate, water, energy, food security and other key challenges of the 21st century … by finding solutions to one problem that are solutions to all.”

With such a sweeping agenda, some greens are nervous that conservatives will have little trouble cherry-picking their own meaning from the summit.

“It’s a welcome objective, but if it goes into resurrecting ideas about creating a new world environmental organization or a comprehensive environmental entity, I think it will be very difficult to make progress,” said Jennifer Haverkamp, international climate director at the Environmental Defense Fund and a former Clinton-era U.S. trade official.

Aside from the Rio conference, Obama faces even more demands over the next year connected to the continued struggle for a way forward on U.N.-led climate negotiations.

Two years after the Copenhagen conference fizzled, talks are set to resume in November in Durban, South Africa.

Calls for a new pact to succeed the 1997 Kyoto Protocol have hit a wall as developed and developing countries square off over how big of a commitment each should make, whether it should be mandatory and how to connect financial aid to the whole package.

Environmentalists aren’t thrilled with the slow pace of the negotiations and on occasion have started showing frustration with an administration that has other priorities to address over the next year and a half.

“The only way to address the climate crisis will be with a global agreement that in one way or another puts a price on carbon,” former Vice President Al Gore wrote last month in a Rolling Stone essay. “And whatever approach is eventually chosen, the U.S. simply must provide leadership by changing our own policy.”

Even without passage of a cap-and-trade bill, U.S. officials say Obama stands by his commitment to reduce emissions 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020. Obama is also still pledging to help developing countries by contributing to a pair of green technology and adaptation funds, although final figures remain a work in progress.

“It’s always important for us, for the United States, to be seen as taking action,” U.S. climate change envoy Todd Stern told POLITICO. “We’ve done a lot under President Obama. We’ve not done as much as we’d liked to had our legislation succeeded.”

No comments:

Post a Comment