As Ban Ki-moon begins his second term asUnited Nations Secretary General, he has come under withering criticism from within the world organization over the way he hires and replaces top managers.

In a remarkably harsh report, a special U.N. investigative unit has charged that the way Ban chooses his most important managers is shrouded in excessive secrecy, that he keeps U.N. member states in the dark about top job vacancies, that he has created elaborate and arcane titles and functions, and skimps on detailed reference checks that could determine whether top officeholders are qualified to do their jobs.

Moreover, the inspectors say, the selection process has become so cumbersome that “appointments are not always made on time,” there is “almost no overlap between incumbents,” and that “ positions are vacant for long periods of time.”

They also charge that Ban’s methods are a step backward from the ways of his predecessor, Kofi Annan, who had promised to shed more daylight on the hiring process.

The two authors of the report, members of a small, elite U.N. evaluation team known as the Joint Inspection Unit, apparently had first-hand experience with Ban’s secretive habits.

They charge that Ban’s executive office stonewalled them in their mandated investigation of his hiring practices, refused them access to personnel files, proposed changes to their recommendations that would, as they put it, “simply eviscerate the entire report,” and contrary to normal practice refused to allow the authors to publish the Secretary General’s comments on their report.

In an extraordinary pushback against Ban’s tactics, the JIU inspectors encouraged U.N. member governments, for whom, in theory, Ban works, to ask the Secretary General to disgorge the withheld information for their own examination.

Click here to read the report.

In complaining about the “opaque” hiring process, the JIU authors, in typically ponderous U.N. prose, declared that “discretionary authority does not mean that the Secretary-General has carte blanche to avoid the process that he has established [for hiring]; discretionary authority should not be used as an excuse to avoid transparency in that process.”

The JIU report was apparently handed over to Ban and U.N. member states in April.

The JIU is a specialized watchdog unit whose members are elected by the General Assembly, and is the only branch of the U.N. that is mandated to assess and improve the efficiency and coordination of the U.N. worldwide, across its entire sprawling array of organizations, funds, programs and agencies.

The inspectors who prepared the report on Ban’s hiring were especially noteworthy, given the document’s complaints about Ban’s adversarial treatment. They were the JIU chairman, Mohamed Mounir Zahran, and the unit’s sole American member, M. Deborah Wynes, a former senior U.S. State Department official who at one time managed all of Washington’s efforts at budgetary and management reform of the U.N.

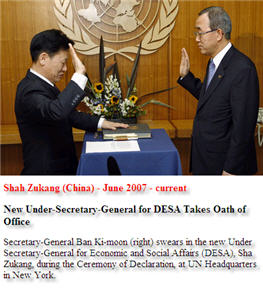

This time, the unit has taken aim at one of the Secretary General’s most important patronage powers: the selection of the top-ranking Under Secretaries General and Assistant Secretaries General who run the U.N.’s various divisions and departments, and wield effective power in the bulky bureaucracy, as well as a variety of special envoys.

The JIU report covers no fewer than 153 top officials at the Secretariat. Those assignments are eagerly sought by national governments on behalf of their citizens who are ostensibly neutral international civil servants, both for the prestige, and because they give favored nations an important, albeit indirect, role in setting U.N. policy.

(For many years, for example, the top post in the U.N.’s Department of Management was held by a U.S. citizen. Now, it is held by a German.)

The JIU report does not intend to upset the appointment apple-cart. “Both the Member States and the Inspectors recognize the explicit discretionary power of the Secretary-General in making senior manager appointments,” the report declares.

The JIU watchdogs made clear, however, that both the number and the nature of Ban’s senior appointments was questionable. “The Inspectors discovered during this review innumerable Under-Secretary and Assistant Secretary-General positions and titles,” they declared, “and sought definitions from the [executive office] in an effort to provide an understanding and clarification among them.” Even after they got the information, “the Inspectors believe there is a clear need to rationalize and streamline the number and title of these positions.”

Along with the number and nature of his hires, the inspectors also took issue with Ban’s “implementation of the process,” which is so circumspect that “many question how the process actually works.” They also fear that the behind-the-scenes selection process makes the U.N. vulnerable to hiring candidates, as the report delicately puts it, “whose qualifications may not be suitable for a particular vacancy.”

That wording is extremely diplomatic compared to a previous JIU report on the hiring of the very top bosses of U.N. organizations, issued in 2009, which felt the need to suggest that U.N. organizations should prohibit “unethical practices such as promises, favors, invitations, gifts, etc., provided by candidates for the post of executive head or their supporting governments during the selection/election campaign, in return for favorable votes for certain candidates.”

In this most recent report, the inspectors note that candidates for top jobs are not screened through a normal human resources process, but instead are interviewed by panels of Ban’s closest advisors, with occasional outside help, which produce three-person short lists for Ban’s final selection. The high-level panels are too august to perform basic screening tasks, such as reference checks, and the inspectors recommended that lower-level human resource professionals take up those tasks in advance.

Another complaint is that Ban’s office is apparently selective in letting various nations know what positions are available, and some have complained that they did not receive notice for each vacancy. Ban’s office contests that view, but the Inspectors found that the complaints were accurate when it came to high-level positions outside New York headquarters.

As one remedy, the inspectors suggested that Ban’s office create, in effect, a “Help Wanted” website to announce vacancies and “convey information on senior appointments to Member States and potential candidates.”

The JIU officials pointed note that Ban’s predecessor, Kofi Annan, promised “a framework and process for the open and transparent nomination and selection procedure for senior management positions,” and that a U.N. budget committee “considers that insufficient progress has been made in implementing this approach.”

What Ban and his executive office explicitly thought of those ideas is not known—precisely, the JIU inspectors say, because of the office’s extraordinary insistence that even its reaction to the JIU’s ideas be kept secret.

But even if all the details of Ban’s reaction are under wraps, it’s not hard to get the general idea. Among other things, the report says, “the Inspectors must point out their regret that, overall, the day-to-day cooperation of the Executive Office of the Secretary-General (EOSG) was not good. A number of submissions in response to the team’s requests were incomplete, ignored or simply were not provided despite numerous reminders.”

The inspectors recount that various personnel files, intended to be viewed as samples, were kept out of their hands until the JIU prepared to note the fact in their annual report to the General Assembly.

Then Ban’s office suddenly decided that the files could be “made available to the Geneva-based Inspectors in a designated room in New York”—provided the inspectors paid for the trip to view them.

That treatment clearly left the inspectors unhappy. The Secretariat’s behavior “serves the Secretary-General poorly and gives credence to the notion that there is a culture of secrecy,” they observed.

But as the report made clear, Ban’s office did not intend to do anything about it—except, perhaps, impose more secrecy. In rejecting his office’s still-secret comments on their report, the inspectors said only that they would “take the Secretariat back to square one and maintain the status quo.”

As for the demand that Ban’s comments also remain secret, the inspectors said they would honor it even though they could find “nothing” in the comments that warranted such treatment, nor any rationale even in the Secretary General’s own published guidelines for handling sensitive material.

Ban’s office was queried by Fox News about the report late last week, but at the time this story was published, had not sent a reply.

George Russell is executive editor of Fox News and can be found on Twitter @GeorgeRussell.

No comments:

Post a Comment